- Home

- Ben Woollard

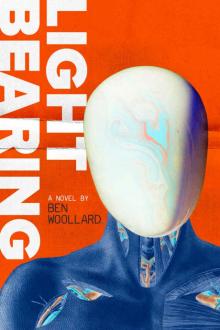

Light Bearing

Light Bearing Read online

Light Bearing

A Novel

Ben Woollard

Copyright © by Ben Woollard. All Rights Reserved

Table of Contents

Part 1:

Prologue:

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Part 2:

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Prologue

The sky is swollen, pregnant with firmament dripping, shimmering silver down over the sounds of a mellow breeze. Insects dwell within the field, flying here, buzzing there, or otherwise adding to the melody of the night. The ecology here is cyclical, all beings taking their due before dissolving down to devourable chunks, overtaken by fungi and bacteria, decomposers, earthworms, maggots, digestive tracks of any number of millions of crawling growing leaping life all diversity simultaneously supporting and destroying itself; regeneration, dissolution, over and over again. Throughout this placid scene runs a division of well packed dirt winding river-like from the hills poised in the distance, feet of giant’s bodies crumbled away while still standing, long gone with the dust storms and erosion of the eons, the time it takes for a trail of silk to wear away a mountain.

A stillness comes over the nocturnal hum, an apparition scattering the cricket drone. There is a foreign entity disturbing the normal run of things. It moves closer, something now approaching from the toes of those megalithic dead, meandering over the gap between two floral oceans. Along the track manifests a bobbing light, a lantern lit by fat of some carcass or another, up and down with the rhythmic gait of nonchalance common to the zen and to the completely hopeless. A figure is visible only as a shadow backlit by the light held from a stick balanced over shoulder. All that is clearly discernable is the raggedness of robes tattered and dirty from incessant travel over harsh terrain. The light bobs up and down, a cork in calm water gently being jostled as if by loving hands. The form stops briefly, peering forward into the darkness and just barely makes out the weak hue of low-level bulbs in the distance.

“Barely enough electricity to illuminate themselves,” the figure whispers, and resumes the methodical bobbing forward, a solitary night marcher. It will not be long now; this march will soon be replaced by something else. The stars look on as the solitary point tracks its way across the field, twinkling color spectrums, stellar Morris code beating undeciphered down to earth.

The settlement is small, not much more than a few disjointed hovels, exposed wiring forming a poorly woven net, seemingly all that keeps the sum of the structures from collapsing, from being overtaken by the system it has been erected upon. A few bulbs form pseudo streetlights over walkways, populated by weatherworn individuals milling about in groups, drinking, smoking various dried plants, telling jokes, all general human mannerisms on display. This is typical for these remote areas, people out here are lucky to have the equipment necessary to generate any electricity, so much of it having been destroyed or lost in the chaos that followed the collapse, the majority of what remained being hoarded in the central settlements. Violence had been rare in the last decades, at least after the initial chaos that ravaged the world as systems balanced, pendulums swinging in wild search for equilibrium, yet still this town or village or whatever arbitrary symbol the inhabitants preferred to use has a makeshift wall surrounding the buildings which stood dead center of expansive hinterlands where food and cattle are cultivated. It was through these supporting outlands that the light now approached the gate, the figure looking up, waiting for somebody to notice. It was not long before the inquisitive face of a man clearly not accustomed to visitors, the gaze held briefly before being joined by a short bark of demand.

“Who are you?” the man asked.

“A traveller,” the figure replied with a smile, “looking to meet the community that calls these hills and fields their home.” The man directed a beam of lantern light down upon the face of the speaker and was greeted by the image of a middle aged woman, her hair shaved to the scalp and a serene look drifting from her features.

“Where do you come from?” the sentry said with a tone of confusion in his voice, visitors were rare, especially women of this age travelling alone by night, and look at her clothes, the man thought, as if she had no regard for her own personal comfort and what’s this, barefoot too? This is a strange sight to see and here he was thinking he would be better off sleeping through the rest of his shift.

“Those such as myself are from nowhere, yet all space is our home, as for where I’ve travelled from that would be the central settlements,” a strange answer that did little to relieve the inquirers growing anxiety. Perhaps this was some kind of trap set by an enemy he was unaware of, but the nearest neighbor was dozens of miles away and there was little point to fighting these days, there only being so many people now and the land having more than enough to offer in these less populated regions.

***

A short time later the woman stood before a small council, the executives of the settlement, those who made the decisions and ran the logistics of the place.

“So you claim to be a missionary for unification through technology but have yet to give an explanation of exactly what that means. You’ll have to forgive us if we are slow to catch on, it’s rare we have any contact with the central settlements and life in these regions is simpler, much less high tech.”

“Of course,” the woman responded, “as you said I have come to bring the light of unification. Since you have not heard of this let me explain: my order has a device capable of melding the consciousnesses of multiple beings into one, creating a single entity. I have come to spread this word, and to invite all who wish to join us in the destiny of the human race.” The council looked uncomfortable, the members gave each other nervous glances; tension filled the room.

“You see,” the woman continued, “when The Device is used upon an individual it permanently alters the neural structure of the brain, effectively synching that persons mind with the unified consciousness, merging them with it. The unification is a field, you see, an energetic structure built in another spatial dimension. Once a persons neurology has been rebuilt correctly they will become a permanent receiver for the signal of this unification.”

“And this device, where does it come from? Who invented it?”

“I built it, or rather the individuals who have become me did, before the collapse and dissolution. These same people were the first to begin merging, dissolving the boundaries of themselves and joining their minds together. This is when I was born, but shortly after my creation the collapse occurred, war broke out everywhere and billions died. But I was not destroyed, I cannot die, my being is in another space, as I have said, and as long as that device exists, and it has survived, I can grow. The way to freedom is through me. Not this body of my previous individual incarnation but the soul of a unifying human race that I have joined, that I now am.”

“So you would have us simply give up our individuality and become you?” The councilor looked hostile, furrowed brow and beady eyes cast upon this dirty woman who stood smiling. “You would have us die to support you, some... thing of which we can’t even be sure of its honesty. “

“I understand your fear,

but you do not understand. Nothing must be destroyed; when minds combine nothing is lost, all contents simply become a part of a new being, one that exists in this new space accessible through The Device. It really is all quite natural, besides, I am offering you immortality, freedom from suffering: this is the natural evolution of humanity. One day the whole of the universe will be populated by a species all sharing a single mind larger than comprehensible even to myself as I currently am.”

“And how can we trust anything you say?”

“I have wisdom beyond any here’s ability to grasp; I have the knowledge of hundreds of lives. But I am not cruel; I understand the difficulties in the decision making of mortals, that things do not appear as clearly to you, your minds lost constantly in confusion and internal struggles within mazes of your own invention. I see many here view me simply as insane, so be it. It may take faith now to trust in the truth that is unification, but soon all will see without doubt that it must be so, I have come simply to spread the word, and to bring those whose hearts have faith into the light. I do not come here threatening violence or coercion, neither are necessary, for no matter how many refuse me or find me an abomination, I am the future and I cannot be resisted.”

“Only as long as The Device exists,” a councilwoman noted, “destroy that and you would die with it, correct?”

“In a sense, but The Device is merely a gateway to entering me, I cannot be destroyed and I do not wither with time, although I am tied to it. If you were to destroy The Device, and I assure you that others have thought of this, it would only delay the inevitable. Besides, why would one want to do such a thing? Why bring war and division when we may all become one. No more of this foolish individuality that plagues the human mind. Why not rather simply allow yourselves to give in and pool all your resources together, all our minds as one, all our souls as one? The entire human race in blissful union forever.” With this the woman bowed, “Violence is a foolishness arising from individuality, so I will respect your decision if you decide to cast me out. I would only ask that you allow me to spread this word throughout the people living here, and that you allow those who so choose to return to the central settlements with me, where they will be joined in holy unification.”

The council was silent, glancing back and forth along each other’s gazes, then back to the figure before them, “we’ll discuss among ourselves and give you a conclusion by morning, until then you may stay here in the council building.” The seated members rose and began to leave. The woman bowed her head respectfully, knowing already there were those among the council who had believed her, and that believers always, sooner or later, chose unification.

Part 1

Chapter 1

It started slow, like a downward pressing heat, imperceptible at first, rumors whispered in the streets and alleys, strange reports from people returning from the outer settlements, but nothing any of us payed any attention to. We had our own lives, our own struggles, and the rambled talk of vagrants was the furthest thing from anyone’s mind. Grandpa used to tell me, he said Sam, society has always gone up and down; it’s a spiraling cycle of chaos, just keep your head down and look out for your own. Then he would laugh, cackling demonic from his throat, eyes bloodshot. He had lived through the collapse, was one of the few who could still remember the time before, albeit just barely. He’d only been nine when it started. Momma said that’s why he was like that, she said everyone lost hope after things fell apart, that people like Grandpa grew up in a time when all anyone could hope for was not to starve or get caught up in the violence of it all, everyone wondering over the continent in bewildered tribes. Back then history seemed so far away from me, like some long dead myth I never really believed in, so lolled as I was by the apparent stability of Columbia, before I knew how fast the world could change and crumble. Nowadays I can’t help but think about the past, it’s a specter that constantly floats near me, fills my mind with regret and sorrow for the way the world seems to conspire against itself, turning everything to ash. It’s like something inside people can’t change no matter what the circumstances, everyone just grinding forward unaware they’re the cause of their own suffering.

Back then life wasn’t easy, but it wasn’t like it was so hard either. Me and my brother Shiloh would spend our days on the outskirts of Columbia, looking through the old dilapidated buildings and piles of trash; foraging for any kind of tech or scrap metal we could dig up. Mostly all we found was plastic, seemed like everything in the old world was made of the stuff. I always hated the way it felt: like solidified mud. Grandpa told us it was made out of some kind of oil they used to suck up from deep within the earth using all kinds of machinery. He said there was a lot of outcry about it because people thought we were gonna bleed the planet dry, suck out every last barrel of its blood just to satisfy our own greed. I never payed much attention to his stories, though, thinking he liked to embellish on things he didn’t really know that much about. How could someone who was only nine when the collapse came know anything about the old world? I couldn’t tell him that, though, and Shiloh always listened, sitting at Grandpa’s feet for hours while he spouted tales of freeways and the interweb, the greatest invention ever conceived, Grandpa would say, sarcasm heavy on his lips. It united all of mankind in a single network, he said, everyone could talk to everyone else, space and time were no longer a factor, and all anyone used it for was pleasure and complaining. Shiloh loved those old stories, loved any story, really, always bright eyed and optimistic, taking everything anyone told him straight to heart. It was the same with the stories Momma used to tell us about the other place. Not the old world, but the one that was always parallel and interwoven with ours. She said that’s where the spirits live. Momma would tell us how everything in the world had a spirit that existed in this other space that overlapped with the one we live in, but could only be seen by a special few, or when the spirits decided they wanted to show themselves. She always tried her best to pass those stories on to us, to preserve the remnants of a time long before the collapse, before the rise that lead to it.

I would say I didn’t believe in any of it, thought it was all bullshit made up to make people feel better about the emptiness of their lives, but I’d be lying if I said that despite my skepticism I didn’t occasionally get a glimpse of something out the corner of my eye, which would disappear as soon as I turned to look, dancing silhouettes of light and shadow just outside my reach. Shiloh believed it all, of course, even said he could see them sometimes, said they would come to him while he slept and tell him things, whisper stories in his ear about the beings who lived in the woods and rivers that had grown to cover all of what used to be the United States, plants sprouting up over every ruin and rusted out vehicle left abandoned in the aftermath.

Momma was tough, and formed the center of our tribe. She’d seen a lot of hard times; it wasn’t easy being born into the decades following the collapse. Her, Grandpa and Grandma had wandered from place to place, living off the land, joining what little bivouac settlements had popped up for a while before moving on. Grandma had died when Momma was only six, stepped on a nail and got an infection so bad the wound had black strings spreading out like spider webs until they grabbed her heart and killed her. Momma and Grandpa had watched it happen, been unable to do anything, travelling as they were and not having access to any type of antiseptic. Momma said she’d cried and screamed at Grandpa, beating on his chest, demanding to know why they had to keep moving so much. It was Grandpa who made them keep leaving every settlement they found, see. He said they had the opportunity to be free and they were gonna take advantage of it, said they wouldn’t stay in one place until they found a life that suited them. After Grandma died, though, his temperament changed, and he realized the pain he’d been putting his family through. He decided right then and there that his selfish ways were through; they came to Columbia, called Milton then, and hadn’t left since.

Momma had me when she only sixteen, and Shiloh was born a year

and half later. My father was some roadster, moving from place to place taking any odd jobs he could find. He told Momma he was in love, that he would settle down with her, stay in Columbia, abandon the nomad life. After Shiloh was born, though, with barely enough money to keep a roof over their heads, and the constant fighting him and Momma’d taken to, he just up and left one day, not so much as a note or a goodbye. Momma said he’d become a drinker, thought he was probably dead now, face down in a ditch somewhere bleeding his stomach through his mouth. When he left we had to move back in with Grandpa, though as time went on it was more like he lived with us than the other way round, being too old to work and spending most his time down at Café Noir talking shit with the other dust piles who hung out there, flirting with old ladies who had too much time on their hands to spend talking about the past.

Momma worked twelve hours a day down at the weaving center, hand making hats and coats for the rich Gov wives and their spoiled offspring. By the time I was ten, and Shiloh nine, we were already helping to support the family, going out to the edges to collect scraps in the rubble, that being the quickest way for a kid to earn money since most places who employed children barely payed them enough to buy a snack on the way home. After a while we became pretty good at scavenging too, to the point where neither of us thought much about looking for other work; it was our trade, in a sense. We did have to go to school for while, Gov required everyone to attend for at least three years, so we could read and write, though mostly we learned through reciting Gov propaganda about progress and the terror of the frailty of the foundations Columbia was built upon. The Gov, or United Central Government, had promised to change all that, of course, said they would implement minimum wages, make Columbia prosperous for all, but as far as I could tell the only ones with any money were the people with ties to the Gov. Still, almost everyone agreed that they had made life better than it was before, even Grandpa, who hated the Gov more than anyone I knew. He said before the conglomeration of the three neighborhoods of Fairfield, Rochester, and Milton into Columbia there was no way for anyone to hold anyone else accountable for the trouble they caused. There were the typical town councils, but they only cared about making sure they stayed in power. At least with the Gov there was law and somebody to enforce it.

Light Bearing

Light Bearing